A Great War and Two Great Writers

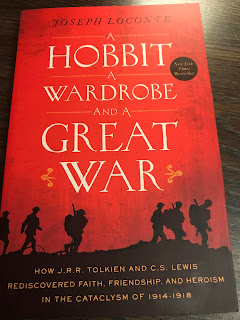

A few days after the COVID-19 shutdown, I bought this book. I figured it would provide hope in facing a crisis. After reading about 90% of it, I stalled. Then, with tomorrow being Memorial Day, I thought it would be good to finish it up and then blog about it. The kayaking trip can wait a week. Or, it may be gone forever as a blog topic. Who knows.

The day that we got word, Friday, March 13, that the schools were closing the following Monday, a casualty of that close-down was the SAT on March 14. Technically, before the close-down order was going into effect. We were one of the last high schools in the area to cancel the SAT. I knew that it would affect over 150 students who needed to take the test as a part of their college planning process. I will save for another day whether these tests (SAT and ACT) should have the weight they do. But, the reality is that they are important. And pulling a test should be done with great circumspection and caution.

The shut-down has obviously imposed a great amount of hardship. First, to the 100,000 who have died and their families and friends. And for all of us--a degree, and a disproportionate amount on small business owners and their employees. And the decision to cancel the SAT is also presenting a significant, albeit less serious hardship. In the back of my mind, though, I thought if one kid's grandparent died because we decided to go ahead with the testing, it was a no-brainer. We didn't have that right, period. We were facing a lot of uncertainty. In fact, in the previous week, I am pretty sure I had COVID-19. And I was all in and all over the materials.

In the community where I work, most of my students' grandparents live close-by and play an important role in their lives. I can't remember at the high school I attended, grandparents playing such an important role. In fact, grandparents often play a crucial role. The thought that one of my kids losing a grandparent from COVID-19 weighed on me heavily and allowed me to be at peace with the decision.

Interestingly, this book played into my grandfather's story, my dad's dad. He was a veteran of World War I and had fought for Germany. His older brother was killed in the war and my grandmother (dad's mom) had lived as a teenager through the war in Germany. Both immigrated after World War I to the U.S., met here, and married. So at least some of this history is personal.

In reading about what Tolkien and Lewis had gone through with the death and destruction of World War I permitted me a glimpse perhaps into what Opa (grandfather in German) had faced.The 20th century was first seen as a step of triumph of science over superstition. Technological progress promised a bright new day until that brightness was the machine gun afire. Trench warfare revealed the depths of human depravity and desperation. Neither side had imagined a war so awful. Yet, like most things tragic, costs are rarely known ahead of time. For many, faith in religion died in the fields of war, poisoned by the gas of skepticism. Faith, however, also died in the belief of technical progress. If all it wrought was unseen and unheard of destruction, we'd be better off better fighting with sticks and stones.

In the word of the author towards the end of the book, "The Will to Power remained a permanent feature of the human predicament. The struggle between Good and Evil would not be resolved within human history. What, then, was the basis for hope?"

Tolkien went into World War I a faithful Catholic. And although his faith was tested in battle and him losing almost all of his close male friends at university in the war, he came out of the other side with an enhanced belief in both good and evil. Lewis, on the other hand, was a skeptic before going to war. Losing his mother as a young child no doubt played a role in his questioning the goodness of God and God's existence period. Lewis too was deeply affected by war. His eyes had seen much that could not be unseen. Neither were spared a full measure.

Later, Tolkien played a crucial role in C.S. Lewis's conversion in seeing that all the great myths were mirrors of a bigger story of redemption, that is a part of our lost but not forgotten Edenic nature, echoes of a perfect world gone astray. And the Return of the King, both central themes in both Lord of the Rings and the Chronicles of Narnia. Both Tolkien and Lewis write in a way that neither denies the reality of evil nor the possibilities of goodness triumphing, although bloodied and scarred. Again, the author of the book Joseph Laconte writes, "Indeed, the most compelling personalities in their stories face down their fears and find themselves transformed by the crisis of their age." Tolkien and Lewis had to first believe this about themselves before they could put it into their characters.

C.S. Lewis's World War II lectures on the BBC became the basis for his highly-influential book Mere Christianity. Whereas World War I was much more ambiguous on which side was more moral, World War II and the rise of Nazism, an ideology fueled by hatred and retribution, the lines of the Western Front at least, were clearer. Lewis was a beacon of hope to Britain.

Opa was not a religious man. He'd drop Oma off at her Catholic Church service and wait in the car I suppose. His experiences in war had seemed to stamp some innocence out of him I surmise. I still remember him walking me down to the park as a young child to ride the swings. If my memory is correct, it was St. Louis, and I think it was, I was no more than four at the time. It had to be St. Louis as I know a park was close-by. I have a memory of missing a rung on the monkey bars and crashing into the asphalt chin first (I still have the scar). Two older kids carried me home, one holding my arms and the other my legs, and knocked on the door of our house with me semi-conscious and bloody stretched out in the front yard. My lack of depth perception no doubt played a role in my missing the rung.

I recollect that one time that Opa took me to the swings either there or in New York City where he lived (I do think it was St. Louis, though, when they visited). There was a silent compassion that he had. He wasn't talkative from what I recall. Just a touch of his hand upon my shoulder as he pushed me on the swing. It was a hand that had held the weapons of war yet now conveyed caring to a four year old child. Something really profound happened in those transactions for I wouldn't remember it more than half a century later if it has not touched me. The hands that harm can become the hands that heal, for both the giver and receiver. Good triumphing over evil.

Comments